Author: akshay

-

Public Health is Bullshit

If a clinician treats tuberculosis with Paracetamol alone, they would be labeled an idiot. Tuberculosis is a disease caused by microorganisms. But also tuberculosis disproportionately affects people who live in poverty and undernutrition. Thus treating TB requires anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) and also nutritional rehabilitation. Paracetamol might help with the symptoms, but is not sufficient. The…

-

Where Time Takes a Break

Swathi and I went to Puducherry this weekend. Just to take a break. Day 0 We left on Thursday night in KSRTC’s AC sleeper from Bengaluru’s Shanthinagar bus stand. It was the old white Ambari Dream Class bus. (Earlier this month when we went to Kerala, we had gotten Ambari Utsav for the first time).…

-

1kg Equity Please

When there is a power-cut and kids are annoyed, we tell them “Here’s 10 rupees, go to the shop and buy 1kg current (electricity)” The kids immediately get it. You can’t purchase electricity like that. It is not an off-the-shelf good. But when it comes to equity (equity as in “Diversity, Equity, Inclusion”, not the…

-

The World is Malleable

TW: Mentions a techbro There is a 90 second video of Steve Jobs on the internet from the time SJ had a beard and lots of hair. In that, in less than 2 minutes, Steve Jobs makes an elevator pitch for a life that’s full of agency. I’m embedding it here so you can watch…

-

Paying Domestic Worker

In my previous post I wrote about how much capital I know I have. In this I tackle another question that might be interesting to people to compare their situations — how much we pay the domestic worker who works in our home and how did we reach that number. I have written earlier about…

-

Capital

It was three years ago in November 2022 that I last wrote about my financial situation. That post ended with my bank balance at around 11 lakhs. I left Kinara capital in June 2023, and then I perhaps had around 20 lakhs if I put everything together. From then, I was spending more money than…

-

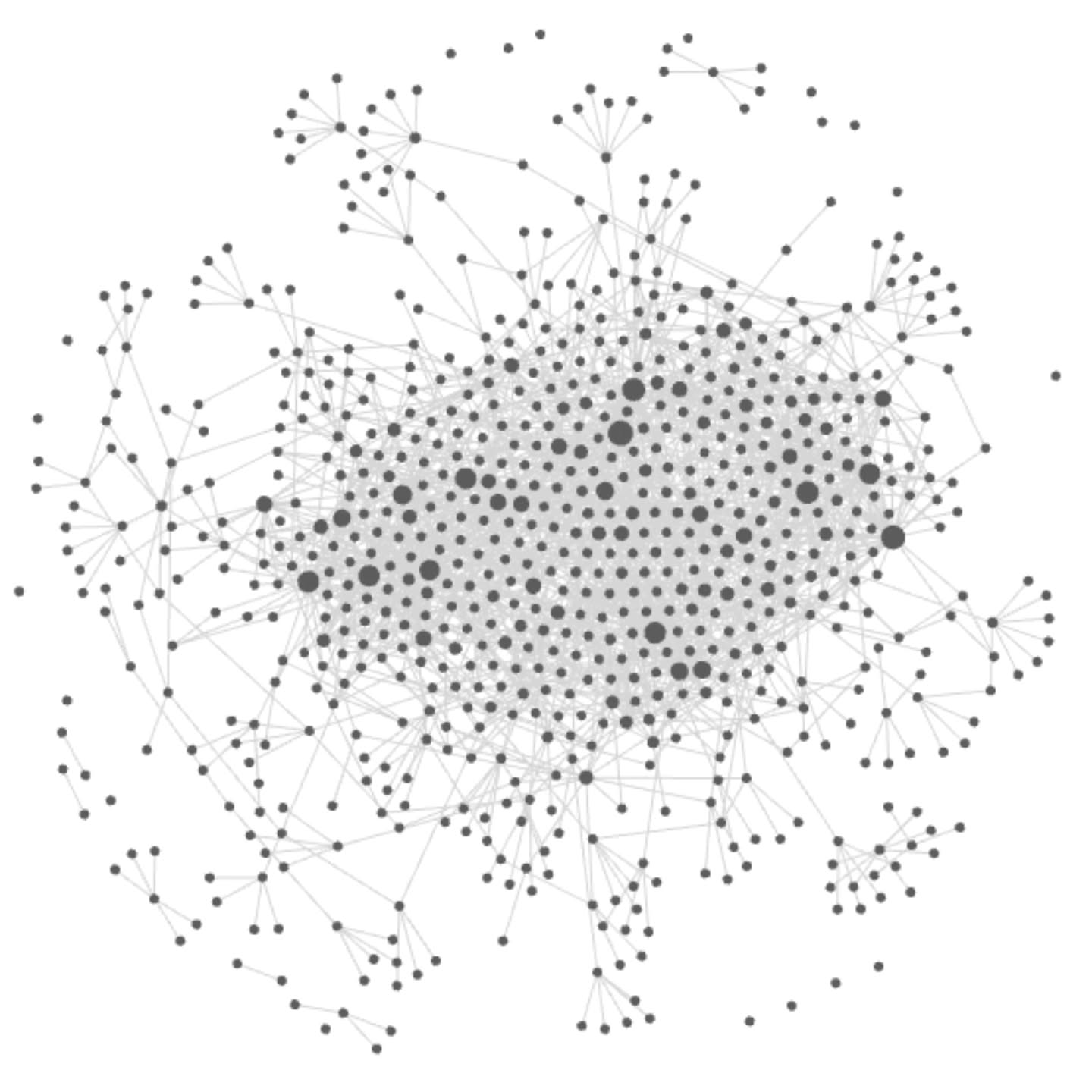

Visualizing Annotated Bibliographies — Story of Kaanu

Last year in August, Kaanu was launched in BR Hills. Kaanu is a South Indian Adivasi Knowledge Centre. The people behind Kaanu has been collecting and annotating relevant publications for many years now. This had to come online and that’s how I got involved. Obsidian Prashanth and Werner had already been curating and annotating a…

-

Privacy is not the Goal

In and around free software circles there are several activists who fight tooth and nail for privacy. They frequently take extreme measures to protect their privacy, like avoiding all kinds of conveniences, and sticking to workflows and tools that majority of people do not use. I am quite uncomfortable with such “privacy-maximization” movements. There are…

-

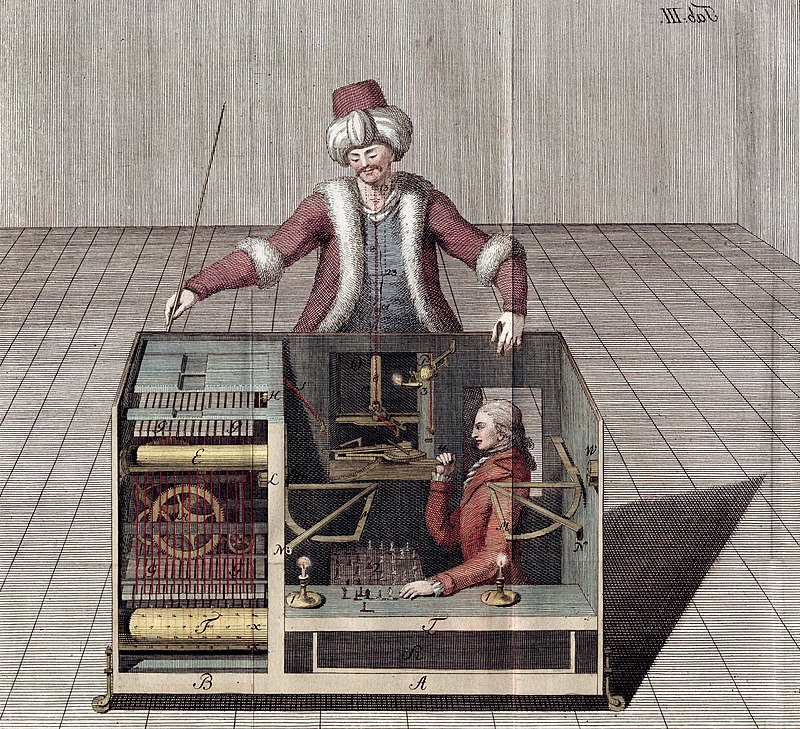

21st Century Humans Are Incredibly Easy to Fool

The 18th century chess machine called The Mechanical Turk fooled humans for almost 84 years. It was a human secretly sitting inside the machine who was playing chess — no machine, no artificial intelligence. If something like that came up today, would we find out the secret sooner? Absolutely not. At any moment in time…

-

A Bigger Microscope Won’t Solve The Problem

In the article titled Johann Gregor Mendel: the victory of statistics over human imagination, the authors argue that big data analysis using machine learning, deep learning, et al can identify patterns that human beings can’t and hence these become “an important tool for developing more effective therapeutic strategies for complex diseases”. Let us examine whether…